The FBI's Double Agent

The Informant at the Heart of the Gretchen Whitmer Kidnapping Plot Was a Liability. So Federal Agents Shut Him Up.

Eric L. VanDussen co-wrote this story with me for The Intercept.

A MONTH BEFORE the 2020 presidential election, the Justice Department announced that the FBI had foiled a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, whose pandemic lockdown measures drew harsh criticism from President Donald Trump and his supporters.

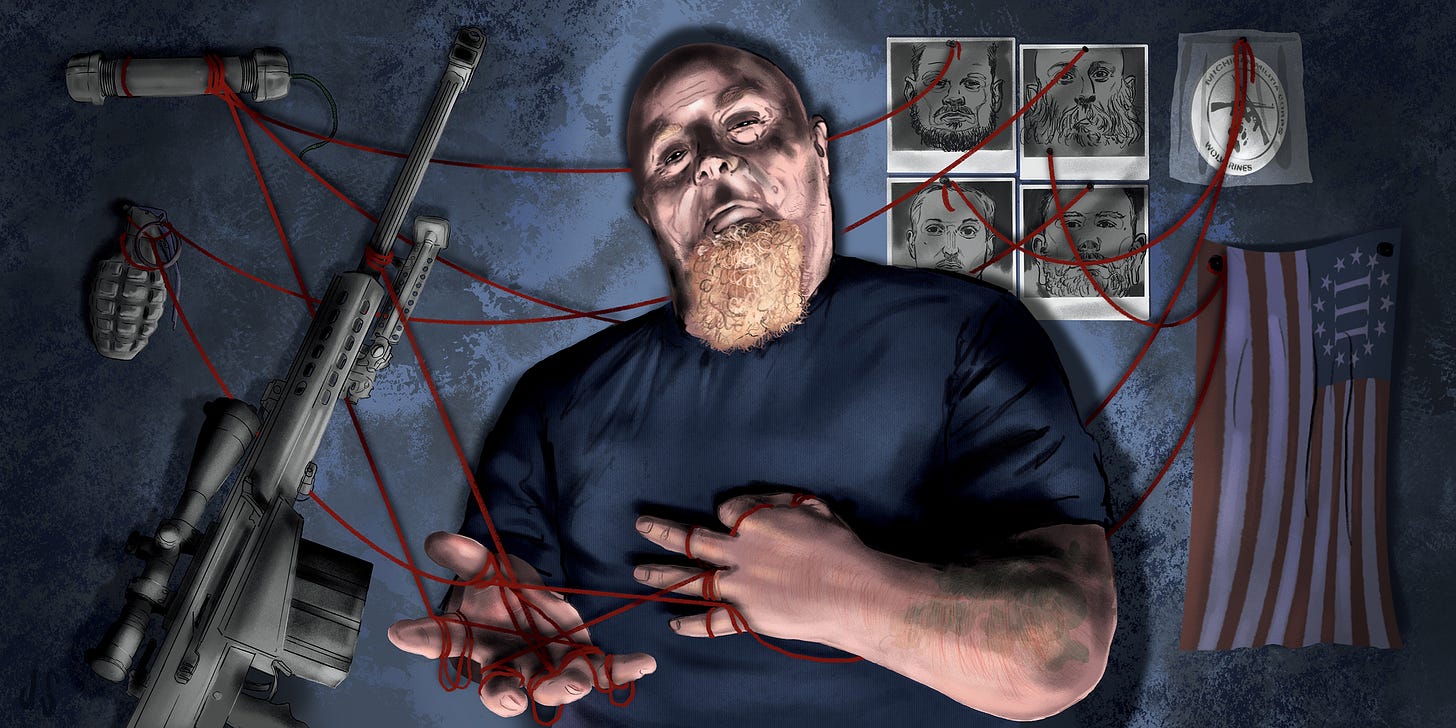

The alleged plot coincided with growing concern about far-right political violence in America. But the FBI quickly realized it had a problem: A key informant in the case, a career snitch with a long rap sheet, had helped to orchestrate the kidnapping plot. During the undercover sting, the FBI ignored crimes that the informant, Stephen Robeson, appeared to have committed, including fraud and illegal possession of a sniper rifle.

The Whitmer kidnapping case followed a pattern familiar from hundreds of previous FBI counterterrorism stings that have targeted Muslims in the post-9/11 era. Those cases too raised questions about whether the crimes could have happened at all without the prodding of undercover agents and informants.

For the FBI, the stakes in the Whitmer case were high. If defense lawyers learned of Robeson’s role in the kidnapping plot, the FBI agents feared, they’d be accused of entrapment. The collapse of the case, built over nearly a year using as many as a dozen informants, two undercover agents, and bureau field offices in at least four states, would have been a public relations coup for right-wing politicians and news media. Both groups have used the problematic investigation as evidence that the Justice Department has been “weaponized” against conservatives — despite a decadeslong public record proving the opposite — and as fuel for conspiracy theories that the January 6 Capitol riot was engineered by the FBI.

But the truth about the Whitmer kidnapping case is far more complicated. This story is based on thousands of pages of internal FBI reports and more than 250 hours of undercover recordings obtained by The Intercept. The secret files offer an extraordinary view inside a high-profile domestic terrorism investigation, revealing in stark relief how federal agents have turned the war on terror inward, using informant-led stings to chase after potential domestic extremists just as the bureau spent the previous two decades setting up entrapment stings that targeted Muslims in supposed Islamist extremist plots. The files also suggest that federal agents have become reckless, turning a blind eye to public safety risks that, if addressed, could disrupt the government’s cases.

For the FBI, the stakes in the Whitmer case were high. If defense lawyers learned of Robeson’s role in the kidnapping plot, the FBI agents feared, they’d be accused of entrapment. The collapse of the case, built over nearly a year using as many as a dozen informants, two undercover agents, and bureau field offices in at least four states, would have been a public relations coup for right-wing politicians and news media. Both groups have used the problematic investigation as evidence that the Justice Department has been “weaponized” against conservatives — despite a decadeslong public record proving the opposite — and as fuel for conspiracy theories that the January 6 Capitol riot was engineered by the FBI.

But the truth about the Whitmer kidnapping case is far more complicated. This story is based on thousands of pages of internal FBI reports and more than 250 hours of undercover recordings obtained by The Intercept. The secret files offer an extraordinary view inside a high-profile domestic terrorism investigation, revealing in stark relief how federal agents have turned the war on terror inward, using informant-led stings to chase after potential domestic extremists just as the bureau spent the previous two decades setting up entrapment stings that targeted Muslims in supposed Islamist extremist plots. The files also suggest that federal agents have become reckless, turning a blind eye to public safety risks that, if addressed, could disrupt the government’s cases.

The FBI documents and recordings reveal that federal agents at times put Americans in danger as the Whitmer plot metastasized. In one instance, the FBI knew that Wolverine Watchmen militia members would enter the Michigan Capitol with firearms — and agents suspected that one man might even have had a live grenade — but did not stop them. (The grenade turned out to be nonfunctional.) Another time, federal agents intervened when local police officers in Michigan were about to confiscate firearms from two of the FBI’s targets, who were on a terrorist watchlist. Local law enforcement had received reports from concerned citizens who saw the men loading their guns before entering a hardware store.

The files also raise questions about whether the FBI pursued a larger, secret effort to encourage political violence in the run-up to the 2020 election. At least one undercover FBI agent and two informants in the Michigan case were also involved in stings centering on plots to assassinate the governor of Virginia and the attorney general of Colorado.

The FBI refused to answer a list of questions. “Unfortunately, due to ongoing litigation, we are unable to comment,” said Gabrielle Szlenkier, a spokesperson for the FBI in Michigan. Robeson, through his lawyer, also declined to comment.

Federal agents paid Robeson nearly $20,000 to participate in a conspiracy that evolved into a loose plot to kidnap the governor of Michigan, according to the documents. But FBI agents knew that two other informants and some of the defendants in the Whitmer case believed that Robeson was the plot’s true architect.

So on December 10, 2020, agents called Robeson into the FBI’s office in Milwaukee in an apparent attempt to silence him. In an extraordinary five-hour conversation, which FBI agents recorded, one of Robeson’s handlers told him: “A saying we have in my office is, ‘Don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story,’ right?” Despite federal and state trials involving the kidnapping plot, this recording — which goes to the heart of questions about whether the FBI entrapped the would-be kidnappers — was never allowed into evidence. The Intercept exclusively obtained the full recording and is publishing key portions for the first time.

The FBI agents asked Robeson to sign a nondisclosure agreement and proceeded to coach and threaten him to shape his story and ensure that he would never testify before a jury. Their coercion of Robeson undermines the Justice Department’s claim, in court records, that Robeson was a “double agent” whose actions weren’t under the government’s control. The agents also made it clear that they had leverage: They knew Robeson had committed crimes while working for the FBI.

“We know we have power, right?” an FBI agent told Robeson during this meeting. “We know we have leverage. We’re not going to bullshit you.”

Robeson’s role as an informant in the Whitmer kidnapping plot was supposed to be a tightly held secret. FBI agents had written the charging documents to conceal his identity.

But the FBI’s paperwork was sloppy. Supporters of the 14 defendants began to piece together clues from details like the FBI’s descriptions of passengers in a car that had been driven near Whitmer’s vacation home in Antrim County, Michigan. The clues appeared to point to Robeson as a snitch — or, in the FBI’s terminology, a confidential human source. After the October 2020 arrests, a panicked Robeson started calling targets of the FBI investigation and denying that he was an informant.

“So when you call, your intentions are to keep some of the heat off of you, right?” an FBI agent asked Robeson during the December 2020 meeting. “To point people in the other direction?”

“Anywhere but me,” Robeson answered. “Not at anyone specific, just away from me.”

Robeson was talking to Henrik “Hank” Impola and Jayson Chambers, two of the lead FBI agents in the Michigan case. Chambers, who previously played in a rock band that “bases all of its music on the fact that Christians are in a spiritual war,” was the registered owner of a private intelligence company whose purported CEO ran a Twitter account known for right-wing trolling and that appeared to tweet about the Michigan case before it was announced.

The two agents started up a good-cop, bad-cop routine with Robeson. Chambers assured him they had done all they could to conceal his role as an informant. Impola, meanwhile, said they needed to come up with a plausible cover story.